900

Views & Citations10

Likes & Shares

As online reviews grow constantly and influence both consumers’ purchase decisions and hospitality companies’ possibilities. It is therefore important for hotel operators to know how to manage and deal with online guest reviews. However, there is a research gap concerning how to encourage and how to manage online guest reviews in the tourism industry in general and in the hotel industry in particular from hospitality companies’ perspective. Using IPA method, this study investigates the practices used by hotel marketers to encourage and manage online guest reviews through assessing the importance level and usage level of practices and testing the gap between these two levels. 186 self-administrated e-mail questionnaires were distributed to the marketing managers at the 5-star hotels in Egypt. The results indicated a statistically significant negative gap between the level of importance managers assigned to each practice and the usage level of that practice for both encouragement and management practices. Overall, the usage level of practices is lower than the importance level. This finding implied that the hotels and managers did not do a good job in matching practices’ importance with practices’ usage. Hence, there are opportunities for changes and improvement in the Egyptian 5-star hotels. This study provides hotels with valuable implications for improving and developing their online marketing strategies and practices.

INTRODUCTION

Online reviews or recommendations—a form of e-WOM—have become increasingly important due to its strong influence on customers’ final purchasing decisions. This is particularly in the hospitality and tourism domain whose its intangible offerings are difficult to evaluate prior to their consumption and thus greatly dependent on the perceived image and reputation. Online reviews provide customers a more independent and therefore more reliable and up-to-date source of information to decide where to go and what to buy. It helps customers to evaluate alternatives, reduce uncertainty in purchase situations, increase product awareness, provide ideas on traveling; help others to avoid places; help to imagine what a place will be like, and improve the probability of consumers to consider making a booking. Thus, online reviews have become an integral part of the decision making process and the major source of information for consumers (Cox et al., 2009; Gu et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010; O’Connor, 2010; Murphy et al., 2010; Jeong & Jang, 2011; Ye et al., 2011; Litvin & Hoffman, 2012; Wilson et al., 2012; Ekiz et al., 2012; Hernandez-Mendez et al., 2013; Gonzalez et al., 2013; EU, 2014; Cantallops & Salvi, 2014; Zarrad & Debabi, 2015; Tuten & Solomon, 2015; Molinillo et al., 2016).

Furthermore, online reviews also give tourism and hospitality companies the possibility to: shape customers’ awareness, expectations and perceptions, reach out and gain more customers at low cost, predict and affect sales or revenues, effectively improve and develop the new and current products or services, audit company’s image and reputation on the internet, build relationships with customers and facilitate consumer centric marketing, follow up service failures and solve the problems of former visitors, define networking agents, profile customers, understand behavioral patterns and catch up on negative reviews before widely spread, improve customers’ satisfaction from addressing customers’ feedback and provide staff feedback (congratulate and reward after positive review or train after negative review) (Buhalis & Laws, 2008; Gretzel & Yoo, 2008; Vermeulen & Seegers, 2009; Gu et al., 2009; Cakim, 2010; O’Connor, 2010; Zhang et al., 2010; Litvin & Hoffman, 2012; Wilson et al., 2012; Ekiz et al., 2012; Cantallops & Salvi, 2014; Simonson & Rosen, 2014; Zeng & Gerritsen, 2014; Jeong & Jang, 2011; Anderson, 2012; TripAdvisor, 2013; EU, 2014; Kim et al., 2015; Molinillo et al., 2016).

Moreover, statistics showed that there has been a rapid increase in the uptake and use of online reviews in tourism and hotel sector (Anderson, 2012; TripAdvisor, 2013; EU, 2014; Molinillo et al., 2016). An industry survey pointed that review websites are considered the most trusted and useful information sources when researching and planning trips and the vast majority of travellers (93%) indicated that other people’s evaluations on travel review websites influence their travel plans. It also showed that 8 out of 10 consumers tend to trust online reviews as much as personal recommendations. Indeed, nearly all businesses (96%) consider online travel reviews to be of upmost importance in generating bookings and about 80% of them are concerned about the potential impact of negative reviews (TripAdvisor, 2013).

As online reviews grow constantly and influence consumers’ purchase decisions and hospitality companies’ possibilities. It is therefore important for hotel operators to know how to manage and deal with online guest reviews. However, there is a lack of research concerning how to encourage and how to manage online guest reviews in the tourism industry in general and in the hotel industry in particular (know-how) from companies’ perspective (Grönroos, 2007; Litvin et al., 2008; Buhalis & Laws, 2008; Vermeulen & Seegers, 2009; Gu et al., 2009; O’Connor, 2010; Bonner & De Hoog, 2011; Jalilvand et al., 2011; Cantallops & Salvi, 2014; Zeng & Gerritsen, 2014; EU, 2014; Lee et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2015; Molinillo et al., 2016). Consequently, the aim of this study was to investigate the practices used by hotel marketers in Egypt to encourage and manage online guest reviews in order to both benefit from positive reviews and contain harmful negative comments. The results could provide hotels with valuable implications for improving or developing their online marketing strategies and practices.

Research Rational and Gap

Although online review research has been growing, there is a lack of empirical studies that investigate the strategies and practices that managers employ to encourage and manage online guest review in the tourism industry in general and in the hotels industry in particular (Grönroos, 2007; Litvin et al., 2008; Buhalis & Laws, 2008; Vermeulen & Seegers, 2009; Gu et al., 2009; O’Connor, 2010; Bonner & De Hoog, 2011; Jalilvand et al., 2011; Cantallops & Salvi, 2014; Zeng & Gerritsen, 2014; EU, 2014; Lee et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2015; Molinillo et al., 2016). In particular, the following research gaps are identified in literature:

1. There is a lack of research (research gap) concerning how to encourage and how to manage online guest reviews in the tourism industry in general and in the hotel industry in particular (know-how). There is a need for studying the marketing strategies and practices for encouraging and managing guest reviews in electronic environments. Most previous research has been conducted in different industries other than tourism industry.

2. Most previous e-WOM or online review research focused on customers’ perspective (online behaviors) rather than companies’ perspective. This study analyzes online reviews from company’s perspective and more precisely from the hotel marketers’ viewpoint in Egypt.

3. Most E-WOM and online review studies focus on developed countries rather than developing countries. This study is one of the first studies investigating how to encourage and manage online guest reviews in developing countries like Egypt.

4. There is a lack of studies on managing online positive reviews. Most prior studies focused on managing negative online reviews. However, the importance of positive reviews in attracting customers, the empirical research indicated that positive online reviews are not active implemented to the hotel web pages and are not active in e-marketing efforts in general.

5. There are no studies that used IPA method for assessing the gap between importance and usage of practices to encourage & manage online guest reviews from marketers’ viewpoint.

6. The empirical research has shown that most hotels still considered online reviews as an information source (information channel), rather than a strategic marketing possibility (marketing channel). Most hotels does not have a specific e-WOM marketing strategy and do not include strategic implications to their general marketing strategy. Most hotels still focus on satisfying the needs of their guests during the service encounter or real experience.

7. Tourism and service providers face challenges when managing e-WOM or online reviews. a) Difficult to control the big amount and fast diffusion of online reviews being published by consumers. This will probably require a lot of resources, staff knowledge and time consuming to monitor them. b) Difficult to manage the multitude of contents broadcasted by customers through different online communities. c) Difficult to respond to customers’ comments regarding company’s products and services. d) Difficult to target the appropriate online communities and customers when they convey a message represent a serious matter for these companies, and. f) risk of online reviews being dishonest. It is easy to change identities on the Internet and the recommendations can be misleading or out of context. However, these challenges, e-WOM (online review) can be managed and should not be ignored. Hotels need to see it as a possibility and incorporate it into its marketing strategy.

These gaps and challenges put increasing pressures on hotels and hotel marketers to find the marketing strategies and practices to encourage and manage online guest reviews in order to both take advantage of positive reviews and mitigate harmful outcomes of negative reviews and, subsequently, gain competitive advantage. The current study fills these research gaps by investigating the practices used by Egyptian hotel marketers to encourage and manage online guest reviews, through assessing both the importance and usage of these strategies and practices in the Egyptian hotel context.

AIM, OBJECTIVES AND QUESTIONS

The aim of this study is to investigate the marketing practices used to encourage the spread of positive online guest reviews as well as manage positive and negative online guest reviews in the 5-star hotels in Egypt in order to earn from positive recommendations and minimize harmful results of negative recommendations. The study measures two related factors from hotel marketer’s viewpoint: 1) The level of importance of practices to encourage and manage online reviews; 2) The level of performance (actual usage) of these practices. It evaluates if managers know what practices they have to use in encouraging and managing online reviews and if they act accordingly and use these practices. In particular, this study aims to achieve four specific objectives as follows:

1) Assess the importance and usage level of the practices used by hotel marketers to encourage the spread of positive online guest reviews.

2) Assess the importance and usage level of the practices used by hotel marketers to manage the positive and negative online guest reviews.

3) Gauge the Gap between importance and usage of practices that employed to encourage and manage online guest reviews.

In relation to these objectives, the research questions are:

1) How hotel marketers in Egypt encourage the spread of positive online guest reviews?

2) How hotel marketers in Egypt manage positive and negative online guest reviews ?

LITERATURE REVIEW

Word-of-Mouth (WOM)

WOM, abbreviated from “Words of Mouth”, is defined as an “informal person-to-person communication between a perceived non-commercial communicator and receiver regarding a brand, a product, an organization or a service” (Harrison-Walker, 2001, p. 63). WOM is “the process of consumers providing information and opinions that can effect consumer’s ultimate purchasing decision and direct a consumer toward or away from a specific product or service” (Zhou et al., 2013, p. 168). WOM is an offline setting where marketing messages are transferred through personal mediums, circulating from person to person. The influence of WOM is greater than other marketing methods, such as individual selling, printed advertisements, and radio. The key characteristic of WOM is that the sources are independent from commercial influence. It is especially relevant when the product is characterized by experiences due to people search for recommendations to reduce their perceptions of risk. This is very essential in the hotel and tourism industry since the product is being bought prior to consumption and experiences are intangible (Litvin et al., 2008; Gu et al., 2009).

Electronic Word-of-Mouth (e-WOM)

Electronic word of mouth, also known as Online WOM or e-WOM is defined as “any positive or negative statement made by potential, actual or former customers about a product or company, which is made available to a multitude of people and institutions via the Internet” (Hennig-Thurau, et al., 2004, p. 39). These online customers’ statements prove to be higher in credibility, empathy and relevance for customers than firms’ marketing information (Jalilvand et al., 2011). E-WOM can also be defined as “informal communication between consumers through the internet where information about goods, services and sellers are posted” (Litvin et al., 2008, p. 461). Traditional WOM communication only had the potential to reach individuals in a consumer’s proximity, whereas e-WOM information can reach individuals all over the world because of the extensive use of the internet all over the world. e-WOM communication can therefore be a powerful information source and be used within a consumer’s pre-purchase information search process and thus have an impact on consumer’s final purchasing decision (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004; Litvin et al., 2008; Jalilvand et al., 2011).

Sometimes e-WOM is called user generated content (UGC). UGC refer to opinions, referrals, recommendations and rating stated without company influence (Moe & Schweidel, 2012; Wilson et al., 2012). UGC contains a slight alteration from the broader scope of e-WOM. While, e-WOM is all communication posted online by both consumers and companies, UGC consists of e-WOM generated only by the consumer. UGC regards the actual creation of new content, whereas e-WOM is content that is conveyed by users (Cheong & Morrison, 2008). UGC is free from company-elicited messages and solely dependent upon online users to engage in transcribing experiences regarding a variety of products (Kozinets et al., 2010). Prior to experiencing a tourist activity, tourists can seek and consume e-WOM through the use UGC sites. UGC sites are websites where consumers can access communication crafted by other consumers or where they would like to create content. As communication venues are open to consumers to contribute both positive and negative experiences without the usual positive input provided by companies, consumers of written eWOM have built an increased trust level on the content provided by those whom they have never met (Brown et al., 2007).

Online Review

Online review or recommendation is one type of information channel which is described as a product or service evaluation posted on a website (Litvin et al., 2008; Banerjee & Chua, 2014; Tuten & Solomon, 2015). Online review is often described as the most accessible and frequently used form of e-WOM and UGC (Jalilvand et al., 2011; Cantallops & Salvi, 2014). It encompasses the act of write as well as the act of assimilates information provided by others (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004). It consists of positive or negative statements made by consumers about a product or service (Jalilvand et al., 2011). Online review could be considered peer-generated purchase experiences (Mudambi & Schuff, 2010). With regard to hotel and travel, statistics show that there has been a rapid increase in the uptake and use of online reviews in the hotels and tourism sector. Thus, online reviews have become an integral part of the decision making process and the major source of information for consumers (Anderson, 2012; EU, 2014; Molinillo et al., 2016).

Online Communities

Online community—also known as a virtual community, is “a group of people who may or may not meet one another face to face, and who exchange words and ideas through the mediation of computer bulletin boards and networks. Like any other community, it is also a collection of people who adhere to a certain (loose) social contract, and who share certain (electric) interests” (Rheingold, 2008). Online communities enable customers to share and comment their previous experiences and give some advice and feedback to others. This information exchange among customers—traditionally called electronic-Word-of-Mouth (e-WOM)—also named User-generated Content (UGC) (Litvin et al., 2008).

The four main types of UGC sites that have been utilized by tourists can be categorized into the following types: social networking sites (i.e., Facebook), review sites (i.e., TripAdvisor), supplier sites (i.e., hotel websites, tourism organizations) and visual content sharing sites (i.e., Flickr, YouTube) (Murphy et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2012). Theses websites provide consumers with positive as well as negative information about products or services, which can help consumers, make a final purchasing. On guest review websites, customers can actively influence opinions by posting comments online; on the other hand, they may passively consume information posted by others in order to develop their own purchasing decisions (EU, 2014; Molinillo et al., 2016). It also provides service providers with a feedback tool to monitor guest’s reactions and experiences, as well as needed improvements. Consequently, positive or negative online reviews have the power to benefit hotels or damage their image and reputation (Jeong & Jang, 2011). These comments can help companies to understand the needs of their customers and to undertake actions accordingly (Buhalis & Laws, 2008; Litvin et al., 2008; Molinillo et al., 2016). Statistics also reveal that review websites are considered the most trusted and useful sources of information when researching and planning trips. Indeed, the vast majority of travellers indicate that other people’s evaluations on travel review websites influence their travel plans (EU, 2014).

METHODOLOGY

Theoretical Model and Hypotheses

Based on a literature review and in response to research questions, the following framework and hypotheses have been formed (Figure 2). The 10 dimensions and its 47 practices are assumed to be the most appropriate strategy to encourage and manage online guest reviews.

Hypothesis of this study is to test the gap between the importance level and usage level of practices used to encourage and manage online guest reviews, from hotel marketers’ viewpoint. It tests whether the usage level of practices are falling, meeting or exceeding the importance level of these practices. Hence, the null and alternate of Hypothesis are:

§ H0: There is no significant difference between the importance level and the usage level assigned to each practice (A necessity condition for rational and coherent management).

§ H1: There is a significant difference between the importance level and the usage level of assigned to each practice.

This hypothesis tested by Paired T-test Analysis: H0: μ1=μ0 versus H1: μ1 ≠ μ0

Definition of Key Terms

· Online review is guest recommendation or evaluation of hotel services and products on online communities.

· Encouraging is encouraging hotel guests to largely and quickly spread their positive reviews and recommendations on online communities.

· Managing is responding and dealing with positive and negative reviews or comments on online communities.

· Online communities – or virtual communities- are groups of individuals who share interests and interact with one another through the mediation of computer bulletin boards and networks. It enables customers to share and comment their previous experiences and give some advice and feedback to others. The following categories can be distinguished:

1. Social networks sites (Facebook, Twitter, Google+, etc.)

2. Pictures/videos sharing platforms sites (Pinterest, Flicker, Instagram, YouTube, Dailymotion, etc.)

3. Commercial review websites (TripAdvisor, eKomi, Yelp, etc…)

4. Supplier Websites (site of your hotel, a third-party company, competitors, an independent user, tourism organization, Blogs and discussion forums, etc.).

Research Type and Approach

This study is primarily a descriptive-analytical study with qualitative and quantitative approaches. Furthermore, this study used deductive approach, since it explains casual relationships, develops a theory and hypotheses and then designs a research strategy to test the validity of hypotheses against the data. If the data are consistent with the hypothesis then the hypothesis is accepted; if not it is rejected. It is moving works from the more general to the more specific (this call a top-down approach) (Saunders et al., 2015).

This study used two main approaches to data collection namely; desk survey and field survey. The desk survey (literature review) forms an essential aspect of the research since it sets the foundation for the development of field survey instruments using questionnaire and interview. Secondary sources of information were identified and collected in books, articles, and professional periodicals, journals and databases on the subject of the study. The field survey is involved with the collection of primary empirical data. Using IPA methodology, this study adopted a self-administrated e-mail questionnaire as the primary method of quantitative data collection to investigate hotel marketers’ practices to encourage and manage online guest reviews through assessing the importance and usage level of practices. The researcher used survey method because it is the most convenient way to obtain relatively highest participation within a limited time frame. Also, the need for generalization in the findings influenced the choice of questionnaire survey. More specifically, the reason for choosing e-mail questionnaire is mainly due to numerous benefits such as reducing geographical limitations and speeding getting answers. In addition, Email questionnaire do also allow the respondents to write down the answers themselves. The researcher has time to reflect on the answers and keep continuous contact when questions arise (Sekaran & Bougie, 2013; Saunders et al., 2015). The mixed data collection methods provides a way to gain in depth insights and adequately reliable statistics.

Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) Method

IPA was developed by Martilla & James (1977) as a popular managerial tool to facilitate prioritization of improvements and resource allocation. IPA assesses the convergence between the importance of specific attributes and how well a service provider is supplying those identified attributes. The main argument of the IPA model is that matching importance and performance (usage) is the basis of effective management. It assumes that managers through their actions pursue the practices that they perceive to be important. The decision to use the IPA structure and terminology was due to its powerful evaluation to find out attributes that are doing well and attributes that need to be improved. In particular, there are two explicit advantages for hotel managers in applying IPA to their management know-how. First, IPA displayed graphically on a two-dimensional grid that explicitly shows the strengths and weaknesses of the hotel practices being studied. Second, IPA provides useful recommendations for hotel managers or policy makers for developing strategies and practices in the future. This is a useful and effective way for management to identify what problems exist, and why. Typically, IPA involves a 3-step process:

1. Identification of management-influenced attributes associated with a concept. It is usually accomplished via consultation with experts, focus groups or other qualitative techniques.

2. Analysis of attributes based on user data that rates attribute importance and performance.

3. Graphical presentation of the results on a two dimensional grid and four quadrants.

Data Collection Instrument

The questionnaire was built based on IPA method and the conceptual framework drawn from the extant literature. In particular, the final data-collection instrument consisted of 2 parts:

· The first part investigates encouragement practices. It measures the importance level hotel marketers assigned to each practice using a Likert scale of 1-least important to 5-most important. Moreover, this part measured the usage level for each of the same practice using a Likert scale ranging from 1-rarely used to 5-extensively used. It consists of 23 practices representing five dimensions.

· The second part investigates management practices. It measures the importance level hotel marketers assigned to each practice using a Likert scale of 1-least important to 5-most important. Moreover, this part measured the usage level for each of the same practice using a Likert scale ranging from 1-rarely used to 5-extensively used. It consists of 24 practices representing five dimensions.

Questionnaire Reliability, Validity and Objectivity

Validity, reliability and objectivity can be seen as three dimensions of a study’s credibility. Validity is the extent to which it actually measures what it intended to be measured from the beginning. Reliability is the degree of trust and if the result remains the same when being repeated. Objectivity is about the values of a researcher and how much it affects the results (Sekaran & Bougie , 2013; Saunders et al., 2015). The questionnaire were rationing before distribution to the study sample to ensure the validity and reliability of paragraphs:

1. To Verify Content Validity (Believe arbitrators): The first version of survey questionnaire was judged by a group of arbitrators. Interviews with 5 experts in the field of hotel marketing were done. Revisions to the questionnaire were made based on feedback from the arbitrators. The researcher responded to the views of the jury and performed the necessary delete and modify in. Factors or questions with 80% approval and higher were only considered. The result was a revised version of the questionnaire with a smaller set of items. The changes made the statements more specific and easier to understand.

2. To Verify Construct Validity: There are two types of analysis for determining construct validity: (1) Correlational analysis, and (2) Factor analysis (Sekaran & Bougie, 2013). This study calculates the construct validity of the attributes of the questionnaire by surveying it to the initial sample size of 15 respondents of the total members of the study population and it calculates the correlation coefficients between each attribute of the questionnaire and the total score for the domain dimension that belongs to him that attribute. The results showed that the value of the correlation coefficients of practices is ranged between 0.65 and 0.55 and is statistically significant at the level of significance (0.05). Hence, the attributes of each dimension are considered honest and valid to measure its role in posting reviews.

3. To Verify Reliability: The most popular test of inter-item consistency reliability is Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. The higher the coefficient, the better the measuring instrument (Sekaran & Bougie, 2013). The researcher conducted reliability steps on the same initial sample using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The results illustrated that the high reliability coefficients for questionnaire attributes which ranged from 0.61 to 0.69, indicating satisfactory internal consistency. The strong internal consistency reliability for the revised scales indicated that the retained items measure the same constructs, suggesting the possibility of the stability of the results that can result from the tool. Thus, the questionnaire became valid and reliable in its final form for application to the basic study sample.

For ethical considerations, each participant received a cover letter that emphasized the significance of the issue under investigation but also stressed that participation in the study was voluntary. The respondents were advised that the data collected would be used solely for the purpose to address the research topic. There were no anticipated risks to the respondents who participated in the study. The removal of any personal identifying information or data was the means to maintain confidentiality.

Sampling Procedures

The target population of this study was the marketing managers at five-star hotels in Egypt. Comprehensive sample was chosen as the most appropriate sampling technique to get a big sample and thus ensure that the results are significant and generalizable. The reason for choosing only 5-star hotels as the empirical research has shown that only the big or chain hotels have the resources to properly implement e-WOM campaigns and strategies. Also, chain hotels are being marketed, online, by their head offices. Smaller hotels that are not well-known globally might not have the resources to control all information being published (Litvin et al., 2008; Vermeulen & Seegers, 2009).

A total of 186 self-administrated e-mail questionnaires were distributed to 186 marketing managers in 186 five star hotels in Egypt, in December 2016. 138 questionnaires were returned, resulting in a 74% response rate. Fifteen questionnaires were not included because of incompleteness. The valid number of questionnaires for analysis was 123 with response rate was 66%.

DATA ANALYSIS

Analysis of the gathered data used the software SPSS 19.0 and Microsoft Excel 2010. The study used Paired T-test analysis to measure the gap between the importance and usage level of practices employed to encourage and manage online guest reviews. Objectives 1 and 2 were achieved by Mean Analysis and IPA matrix. Objective 3 and study hypothesis were achieved by Paired T-test Analysis. Finally, interpretation of the results was done at 5% level of significance; where the value of p<0.05 was considered as significant and p < 0.01 was considered as highly significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 1 indicates the practices’ importance and usage analysis as well as the gap analysis.

Practices’ Importance and Usage Analysis

When evaluating the encouragement practices, the importance mean scores of the 23 practices varied from 4.22 (the highest) to 3.40 (the lowest) out of a possible range of 1.0 to 5.0, with 1.0 indicating least important and 5.0 indicating most important. However, there was a distinction between the 23 practices and a priority of importance was evident. Overall, the average importance mean of practices was 3.98. It should be noted that twenty practices were perceived as important with a mean greater than or equal to 3.98 (M ≥ 3.98). These practices are related to four dimensions; “sponsor opinion leaders, remind/reward reviewers, use e-WOM campaign and join/use online communities”. This finding implied that marketing managers focus on these practices as the number one of priority. Hotel marketers believed that these practices play a significant role in encouraging online guest reviews. Hence, hotel operators should put in more effort and attention to improve these practices when encouraging online guest reviews. Moreover, it should be noted that only three practices were perceived as moderately important with a mean less than 3.98 (3.98˃M). These practices are related to one dimension; “use online stealth marketing” dimension”. This finding implied that hotel marketers focus on these practices as the number two of priority. It should be noted, however, that these practices were also deemed significant, but to a lesser extent and shouldn't be disregarded when encouraging online reviews.

Meanwhile, the usage mean scores of the 23 practices varied from 3.87 (the highest) to 3.29 (the lowest) out of a possible range of 1.0 to 5.0, with 1.0 indicating rarely used and 5.0 indicating extensively used. However, there was a distinction between the 23 practices and a priority of usage was evident. Overall, the average usage mean of practices was 3.41. It should be noted that six practices were perceived as quite used with a mean greater than or equal to 3.41 (M ≥ 3.41). It should be noted that these practices are related to one dimensions; “join/use online communities”. Hotel marketers perceived these practice as the widely used action in encouraging online reviews. It is the number one of usage priority. This finding implied that hotels’ performance in applying these particular practices is strong. Thus, hotel managers ought to take them into consideration and continue to maintain good standard and shouldn't be ignored. Moreover, it should be noted that 17 practices were perceived as moderately used with a mean less than 3.41 (3.41˃M). It should be noted that these practices are related to four dimensions; “remind/reward reviewers, sponsor opinion leaders, use e-WOM campaign and use stealth marketing”. Hotel marketers perceived these practices as the number two of usage priority. This finding implied that hotels’ performance in applying these particular practices is moderate. Hence, hotel managers should concentrate on these practices and more resources, effort and attention should be spent on improving performance of these practices.

Overall, the rankings in descending order of the importance mean scores of encouragement dimensions were as follow: sponsor opinion leaders (4.20), remind/reward reviewers (4.15), use e-WOM campaign (4.11), join/use online communities (4.04) and use stealth marketing (3.41). Meanwhile, the rankings in descending order of the usage mean of encouragement dimensions were as follow: join/use online communities (3.74), remind/reward reviewers (3.36), sponsor opinion leaders (3.34), use e-WOM campaign (3.32) and use stealth marketing (3.30).

When evaluating the management practices, the importance mean scores of the 24 practices varied from 4.22 (the highest) to 3.43 (the lowest) out of a possible range of 1.0 to 5.0, with 1.0 indicating least important and 5.0 indicating most important. However, there was a distinction between the 24 practices and a priority of importance was evident. Overall, the average importance mean of practices was 3.80. It should be noted that seventeen practices were perceived as important with a mean greater than or equal to 3.80 (M ≥ 3.80). These practices are related to three dimensions; “monitor/track online reviews, respond to negative reviews and respond to positive reviews”. This finding implied that managers focus on these practices as the number one of priority. Hotel marketers believed that these practices play a significant role in influencing their online review management. Hence, hotel operators should focus on these practices and put in more effort and attention to improve these practices when managing online reviews. Moreover, it should be noted that seven practices were perceived as moderately important with a mean less than 3.80 (3.80˃M). These practices are related to two dimensions; “initial quick response and respond to mixed reviews”. This finding implied that hotel marketers focus on these practices as the number two of priority. It should be noted, however, that these practices were also deemed significant, but to a lesser extent and shouldn't be disregarded when managing online reviews.

Meanwhile, the usage mean scores of the 24 practices varied from 3.93 (the highest) to 3.34 (the lowest) out of a possible range of 1.0 to 5.0, with 1.0 indicating rarely used and 5.0 indicating extensively used. However, there was a distinction between the 24 practices and a priority of practices usage was evident. Overall, the average usage mean of practices was 3.49. It should be noted that seven practices were perceived as quite used with a mean greater than or equal to 3.49 (M ≥ 3.49). These practices are related to one dimension; “respond to negative reviews”. Hotel marketers perceived these practice as the widely used action in managing online reviews. It perceived as the number one of usage priority. This finding implied that hotels’ performance in applying these particular practices is strong. Thus, hotel managers ought to take them into consideration and continue to maintain good standard and shouldn’t be ignored. Moreover, it should be noted that 17 practices were perceived as moderately used with a mean less than 3.49 (3.49˃M). These practices are related to four dimensions; “monitor/track online reviews, respond to positive reviews, initial quick response, and respond to mixed reviews”. Hotel marketers perceived these practices as the number two of usage priority. This finding implied that hotels’ performance in applying these particular measures is moderate. Hence, hotel managers should concentrate on these practices and more resources, effort and attention should be spent on improving performance of these practices.

Overall, the rankings in descending order of the importance mean of management dimensions were as follow: monitor/track online reviews (4.11), respond to negative reviews, (4.01), respond to positive reviews (3.89), initial quick response (3.56) and respond to mixed reviews (3.45). Meanwhile, the rankings in descending order of the usage mean of management dimensions were as follow: respond to negative reviews (3.89), monitor/track online reviews (3.42), respond to positive reviews (3.41), initial quick response (3.37) and respond to mixed reviews (3.35).

The Gap Analysis between the Importance and Usage Level of Practices

When evaluating encouragement practices, the mean gap scores for the 23 encouragement practices varied from -0.90** (the highest gap) to 0.11** (the lowest gap). Nevertheless, each practice showed differences with respect to the size and direction of gap score. The mean gap scores for the 23 practices are all statistically significant and negative (at p<0.01). Overall, the average mean gap score was -0.57**. The average usage level of practices (3.41) is lower than the average importance level (3.98). It should be noted that fourteen practices were perceived as the highest gap with a difference greater than or equal to -0.57. It should be noted that these practices are related to three dimensions; “sponsor opinion leaders, remind/reward reviewers, use e-WOM campaign”. This finding implied that these practices are the highest shortfalls in online review encouragement. Hotel marketers should focus on these practices as the number one of priority. Hence, hotel operators should concentrate on these practices and should put in more effort and attention to improve these practices when encouraging online reviews. Moreover, it should be noted that only nine practices were perceived as smallest gap with a difference less than -0.57. These practices are related to two dimensions; “join/use online communities, and use stealth marketing”. This finding implied that these practices represent the lowest shortfalls in encouraging online reviews. Hence, hotel managers should also focus on these dimensions as the number two of priority when managing online reviews.

Meanwhile, when evaluating management practices, the mean gap scores for the 24 management practices varied from -0.83** (the highest gap) to -0.01** (the lowest gap). Nevertheless, each practice showed differences with respect to the size and direction of gap score. The mean gap scores for the 24 practices are all statistically significant and negative (at p<0.01). Overall, the average mean gap score was -0.31**. The average usage level of practices (3.49) is lower than the average importance level (3.80). It should be noted that eleven practices were perceived as the highest gap with a difference greater than or equal to -0.31. It should be noted that these practices are related to two dimensions; “monitor/track online reviews, respond to positive reviews, as well as one practice from “respond to negative reviews” dimension. This finding implied that these practices are the highest shortfalls in online review management. Hotel marketers should focus on these practices as the number one of priority. Hence, hotel operators should put in more effort and attention to improve these practices when managing online reviews. Moreover, it should be noted that thirteen practices were perceived as smallest gap with a difference less than -0.31. These practices are related to three dimensions; “quick initial response, “respond to negative reviews (except one practice)” and “respond to mixed reviews”. This finding implied that these practices represent the lowest shortfalls in managing online reviews. Hence hotel marketers should also focus on these dimensions as the number two of priority when managing online reviews.

Overall, the rankings in descending order of the gap mean scores of encouragement dimensions were as follow: sponsor opinion leaders (-0.86), remind/reward reviewers (-0.79), use e-WOM campaign (-0.79), join/use online communities (-0.30), and use stealth marketing (-0.11). Meanwhile, the rankings in descending order of the gap mean of management dimensions were as follow: monitor/track online reviews (-0.69), respond to positive reviews (-0.48), initial quick response (-0.19), respond to negative reviews (-0.12) and respond to mixed reviews (-0.10).

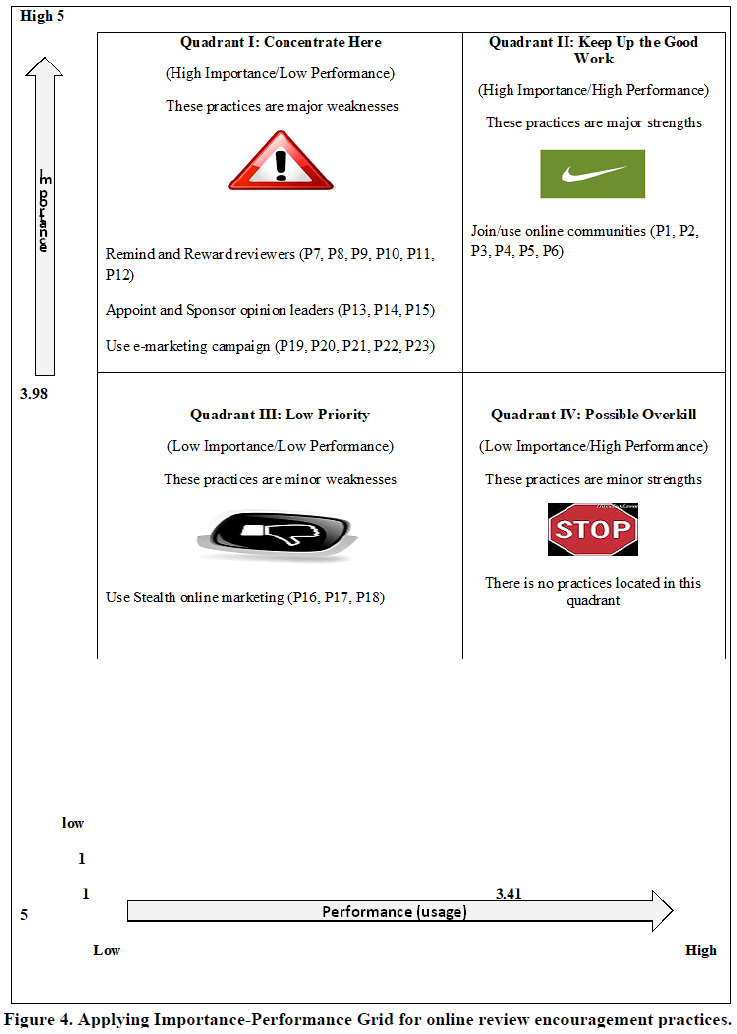

As noted in Figures 3 and 4, IPA assesses the convergence between the importances of specific attributes and how well a service provider is supplying those identified attributes.

Using IPA method, this study measures online review encouragement and management practices from hotel marketers’ viewpoint, through assessing the importance and usage level of practices and testing the gap between the two levels. The results of the paired t-test indicated a statistically significant and negative difference (gap) (p ≤ 0.01) between the level of importance mangers assigned to each practice and the level of usage of that practice for both encouragement and management practices. The average usage level of practices is lower than the average importance level. Overall, the average mean gap score of encouragement practices was -0.57** and the average mean gap score of management practices was -0.31**. Hence, the null hypothesis 1 which proposed an absence of difference was therefore rejected. Meanwhile, the alternate hypothesis 1 which proposed an existence of difference was therefore accepted. There are two observations. First, it should be noted that gaps are all significant, which suggests that at a basic level, there is considerable difference between the practices’ importance and usage. This finding implied that the hotels and marketers did not do a good job in matching practices’ importance with practices’ usage. Hence, there are opportunities for changes and improvement in studied hotels. The existence of significant gaps clearly showed that there is a room for improvement in studied hotels. These gaps were the shortfalls and require the most attention by hotel marketers in their efforts to make some improvement. By understanding and investigating those gaps, it is easier for management to control and take corrective action to reduce the difference between the importance and usage level of practices. Second, it should be noted that all gaps are negative; the usage level is lower than the importance level. A negative score indicated practices which should command more attention and that need to be improved. This finding implied that further improvement resources and efforts should concentrate here. The main argument of the IPA model is that matching importance and usage is the basis of effective management.

The results of IPA matrix provide useful recommendations for hotel marketers or policy makers for improving and developing the strategies and practices of encouraging and managing online guest reviews. It provides insight for future management recommendations for each practice based on its position in one of the four quadrants. Each quadrant implies a different management strategy:

1. The evaluating hotels and marketers should command more attention and improvement efforts to 14 encouragement-practices and 10 management-practices in the “concentrate here” quadrant (High Importance/Low Performance). These practices represents 3 encouragement dimensions (remind/reward reviewers, sponsor opinion leaders, and use e-WOM campaign) and two management dimensions (monitor/track online reviews, and respond to positive reviews). These dimensions and its practices are major weaknesses and require immediate attention for improvement. It represents key areas that need to be improved with top priority. The management scheme for this quadrant is “concentrate here”.

2. The evaluating hotels and marketers should maintain efforts and resources to 6 encouragement-practices and 7 management-practices in the “keep up the good work” quadrant (High Importance/High Performance). These practices represents one encouragement dimensions; join/use online communities and one management dimension; respond to negative reviews. These dimensions and its practices are major strengths and opportunities for achieving competitive advantage. Thus, hotel managers should keep up the good work. The management scheme is “keep up the good work.”

3. The evaluating hotels and marketers should not deserving remedial actions to 3 encouragement-practices and 7 management-practices in the “low priority” quadrant (Low Importance/Low Performance). These practices represents one encouragement dimension; use stealth marketing and two management dimensions; respond to mixed reviews and initial quick response. These practices are minor weaknesses and do not require additional effort. Marketers should expend limited resources and efforts on these practices. The management scheme for this quadrant is “low priority.”

CONTRIBUTIONS

This research study contributes to the existing online review literature by adding to the knowledge a theoretical practices model for encouraging and managing online guest reviews from company’s perspective. This model enables hotel marketers and practitioners to better know and understand how to encourage and manage online reviews to better then influence the customers’ choice during their purchase decision making. Hotels and marketers can actively incorporate these practices in their future online marketing strategy. Considering these practices enable hotels to more efficiency encourage and manage online guest reviews. Additionally this study is one of the first studies investigating how to encourage and manage online guest reviews in the Egyptian context.

But more importantly it also contributes to the hotel practice by adding to the knowledge a practical methodology by which hotel marketers and practitioners can assess and improve their level of online review encouragement and management practices. This study enables hotels and marketers to analyses online review from company’s perspective and more precisely from hotel marketers’ viewpoint. It provides priorities for online review encouragement and management practices to utilize recourses efficiently and direct needed interest to the most fruitful aspects of operation. Hoteliers can easily understand the areas where changes and improvements are needed. It would enable hotels and managers to investigate which practices should require more attention and which may be consuming too many resources on achieving competiveness and effectiveness as a significant way for managing online guest reviews. Additionally, an effective management enables hotels to then improve their online marketing and communication strategy and consequently satisfy customers.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

· The focus of this research is limited to the 5-star hotels in Egypt. Future studies might therefore focus on extending the same examination to other countries, other hotel categories (e.g. 4-star hotels, 3-star hotels) and other service types (e.g. airline, restaurant industries) to improve the robustness of the findings. Research is needed on the relationship between the levels of encouragement or management practices and hotel’s size, star rating, branding or nationality.

· This study used the primary online quantitative questionnaire. It would be interesting future studies to use qualitative approach (i.e., face-to-face interviews) to deeply investigate the participants about the practices used to encourage and manage online guest reviews.

· The practices of online review encouragement and management used in this study do not represent all possible practices that may be taken. The study practices are only suggestions that might be useful when working with online reviews. It is just a guideline—hotel and marketers responses should still be personalized to each review. Not all suggested practices will be relevant or applicable at any specific facility because of the wide variety in the types, sizes, and locations of hotels. The ideal number and structure of practices and dimensions could be different depending on the type of industry, the service firm, the type of online community, or the circumstances under which studies are rendered. To measure the variability among the items (practices) a factor analysis can be used to analyze the relationship between the items and to decide what items can measure the same latent factors.

· Further research can conclude how cultural differences play a role in encouraging and managing online reviews. Further studies may compare practices between different cultures.

· It can be expanded to include a broader application of IPA for a comparison of encouragement and management practices for independent versus chain hotels and 4-star versus 5-star hotels.

· Future research should identify and assess the primary motivators and barriers for encouraging and managing online reviews from hotels’ perspective.

· Future studies focus on how to deal with fake or misleading reviews.

Additional research should focus on these limitations to assure the most precise results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I thank Allah for granting me the guidance, patience, health and determination to successfully accomplish this work. I would like to consider online review in more depth in a forthcoming special issue and would welcome any comments on how this might best be structured.

Anderson, C. (2012). The impact of social media on lodging performance. Cornell Hospitality Report, 12(15), 4-11.

Banerjee, S. & Chua, Y. (2014). A theoretical framework to identify authentic online reviews. Online Information Review, 38(5), 634-649.

Bronner, F. & de Hoog, R. (2011). Vacationers and e-WOM: Who posts and why, where and what? Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 15-26.

Brown, J., Broderick, A. & Lee, N. (2007). Word of mouth communication within online communities: Conceptualizing the online social network. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 27(3), 2-20.

Buhalis, D. & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the internet – the state of e-tourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609-623.

Cakim, I. (2010). Implementing word of mouth marketing: Online strategies to identify influencers, craft stories and draw customers. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Cantallops, A. & Salvi, F. (2014). New consumer behavior: A review of research on e-WOM and hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 56(1), 41-51.

Cheong, H.J. & Morrison, M.A. (2008). Consumers reliance on product information and recommendations found in UGC. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 8(2), 38-49.

Cox, C., Burgess, S., Sellitto, C. & Buultjens, J. (2009). The role of user-generated content in tourists’ travel planning behavior. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 18(9), 743-764.

Ekiz, E., Khoo‐Lattimore, C. & Memarzadeh, F. (2012). Air the anger: Investigating online complaints on luxury hotels. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 3(2), 96-106.

EU (European Union). (2014). Study on online consumer reviews in the hotel sector. Report submitted by: Risk & Policy Analysts (RPA) Ltd., Center for Strategy & Evaluation Services (CSES) and Policy & Development (EPRD). European Commission, 9 June, 2014. Available at: http://bookshop.europa.eu/en/study-on-online-consumer-reviews-in-the-hotel-sector-pbND0414464/downloads/ND-04-14-464-EN-N/ND0414464ENN_002.pdf;pgid=GSPefJMEtXBSR0dT6jbGakZD0000eFVxbhml;sid=NTHy2KloO6vymfHoYP9sf8tNl_KOiAurSWE=?FileName=ND0414464ENN_002.pdf&SKU=ND0414464ENN_PDF&CatalogueNumber=ND-04-14-464-EN-N

Gonzalez, S., Bulchand-Gidumal, J. & Lopez-Valcarcel, B. (2013). Online customer reviews of hotels: As participation increases, better evaluation is obtained. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(3), 274-283.

Gretzel, U. & Yoo, K. (2008). Use and impact of online travel reviews. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, 2, 35-46.

Grönroos, C. (2007). Service management and marketing. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Gu, B., Law, R. & Ye, Q. (2009). The impact of online user reviews on hotel room sales. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(1), 180-182.

Harrison-Walker, L.J. (2001). The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. Journal of Service Research, 4(1), 60-75.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K.P., Walsh, G. & Gremler, D.D. (2004). Electronic word of mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(1), 38-52.

Hernandez-Mendez, J., Munoz-Leiva, F. & Fernandez, J. (2013). The influence of e-word of mouth on travel decision-making: Consumer profiles. Current Issues in Tourism, 1-21.

Jalilvand, M., Esfahani, S. & Samiei, N. (2011). Electronic-of-mouth: Challenges and opportunities. Procedia Computer Science, 3, 42-46.

Jeong, E. & Jang, S. (2011). Restaurant experiences triggering positive electronic word-of mouth (eWOM) motivations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(2), 356-366.

Kim, W.G., Lim, H.J., & Brymer, R.A. (2015). The effectiveness of managing social media on hotel performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 44, 165-171.

Kozinets, R., de Valck, K., Wojnicki, A. & Wilner, S.J.S. (2010). Networked narratives: Understanding word-of-mouth marketing in online communities. Journal of Marketing, 74(2), 71-89.

Lee, M., Rodgers, S. & Kim, M. (2009). Effects of valence and extremity of eWOM on attitude toward the brand and website. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 31(2), 1-11.

Litvin S.W., Goldsmith R. & Pan P. (2008). Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tourism Management, 29(3) 458-468.

Litvin, S. & Hoffinan, L.M. (2012). Responses to consumer-generated media in the hospitality marketplace: An empirical study. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 18(2), 135-145.

Luo, C., Luo, X., Xu, Y., Warkentin, M. & Sia, C. (2015). Examining the moderating role of sense of membership in online review evaluations. Information & Management, 52(3), 305-316.

Martilla, J. & James, J. (1977). Importance-performance analysis. Journal of Marketing, 41(1), 77-79.

Moe, W.W. & Schweidel, D.A. (2012). Online product opinions: Incidence, evaluation and evolution. Marketing Science, 3 (3), 372-386.

Molinillo, S., Ximénez-de-Sandoval, J.L., Fernández-Morales, A. & Coca-Stefaniak, A. (2016). Hotel assessment through social media: The case of TripAdvisor. Tourism & Management Studies, 12(1), 15-24.

Mudambi, S.M. & Schuff, D. (2010). What makes a helpful online review? A study of customer reviews on amazon.Com. MIS Quarterly, 34(1), 185-200.

Murphy, H.C., Gil, E.A.C. & Schegg, R. (2010). An investigation of motivation to share online content by young travelers - Why and where. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, 467-478.

O’Connor, P. (2010). Managing a hotel’s image on TripAdvisor. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 19(1), 754-772.

Rheingold, H. (2008). Virtual communities—exchanging through computer bulletin boards. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, 1(1).

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2015). Research methods for business students. 7th Edn. Pearson, Inc.

Sekaran, U. & Bougie, R. (2013). Research methods for business: A sill building approach. John Wiley & Sons, UK.

Simonson, I. & Rosen, E. (2014). What marketers misunderstand about online reviews. Harvard Business Reviews, 23-25.

TripAdvisor. (2013). TripBarometer by TripAdvisor. The world’s largest accommodation and traveler survey, winter 2012/2013. Available at: http://www.tripadvisortripbarometer.com/download/Global%20Reports/TripBarometer%20by%20TripAdvisor%20%20Global%20Report%20-%20USA.pdf

Tuten, T. & Solomon, M. (2015). Social media marketing. 2nd Edn. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Vermeulen, I.E. & Seegers, D. (2009). Tried and tested: The impact of online hotel reviews on consumer consideration. Tourism Management, 30(1), 123-127.

Wilson, A., Murphy, H. & Fierro, J.C. (2012). Hospitality and travel: The nature and implications of user-generated content. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 53(3), 220-228.

Ye, Q., Law, R., Gu, B. & Chen, W. (2011). The influence of user-generated content on traveler behavior: An empirical investigation on the effects of e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 634-639.

Yoo, K.H. & Gretzel, U. (2008). What motivates consumers to write online travel reviews. Journal of Information Technology & Tourism, 10(4), 283-295.

Zarrad H. & Debabi M. (2015). Analyzing the effect of electronic word of mouth on tourists’ attitude toward destination and travel intention. International Research Journal of Social Sciences, 4(4), 53-60.

Zeng, B. & Gerritsen, R. (2014). What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 10, 27-36.

Zhang, Z., Ye, Q., Law, R. & Li, Y. (2010). The impact of e-word-of-mouth on the online popularity of restaurants: A comparison of consumer reviews and editor reviews. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(4), 694-700.

Zhou, M., Liu, M. & Tang, D. (2013). Do the characteristics of online consumer reviews bias buyers’ purchase intention and product perception? A perspective of review quantity, review quality and negative review consequence. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 19(4), 166-186.V